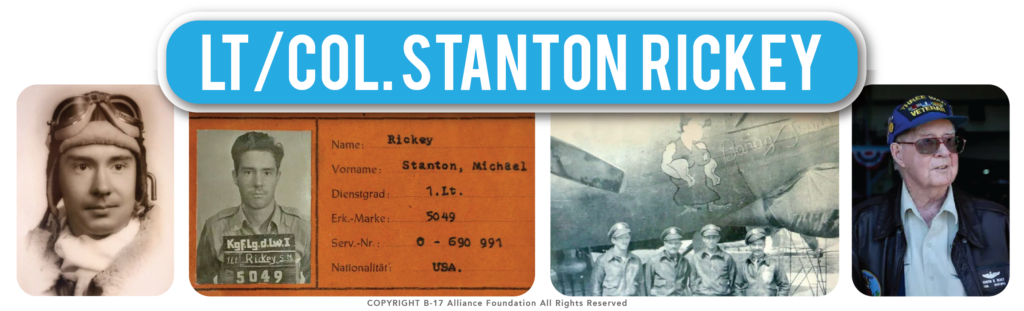

LT/COL. Stanton M. Rickey

World war II – air corps – B-17 flying fortress – pilot/POW

817th Squadron 483rd Bomb Group | Triple War Veteran: World War II, Korea, and Vietnam. (Retired 1971)

OBITUARY: https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/39458932/stanton-michael-rickey

CITATION: Prisoner of War Medal

First Lieutenant (Air Corps) Stanton M. Rickey (ASN: 0-690991), United States Army Air Forces, was captured by German forces after he was shot down on or about July 18, 1944and was held as a Prisoner of War until his return to U.S. Military Control at the end of hostilities in May 1945.

‘A Tough Time of Life’

In a single 24-hour period, Stanton Rickey had his B-17 bomber blown out from under him, bailed out over Germany, “borrowed” civilian clothing from a clothesline to begin a 60-mile journey to Switzerland, and become a father for the first time. Stationed in Italy with the 15th Air Force, 817th Squadron of the 483rd Bombardment Group, the crew of the Baraz Twins II received their orders on July 18, 1944.

The target was the marshaling yards at Memmingen Airfield in southwestern Germany. One hundred sixty-eight B-17s took off from Italy that day, but most turned back due to poor weather. Rickey’s crew was among 26 bombers who continued — without any fighter escort due to a foul up. As they neared the target, they were met by 200 enemy fighter planes. The air battle saw 14 of the 26 “flying fortresses” go down. Sixty-three crewmen were killed in action and 80 were taken as prisoners.

The Baraz Twins II crashed over Kempten, just shy of Memmingen. “My airplane was hit by fighters.” Rickey said. “We lost two engines quickly to cannon fire and the tail section broke off. I tried to keep it as level as I could so the three surviving airmen could get out. I kicked off into a spin and I got out at about 5,000 feet.”

“It was quite a scene — parachutes were coming down everywhere,” said Rickey. “And people were rounding up prisoners.” Rickey himself landed in a tree that becomes taller each time he tells the story. It was the 27th mission for this 23-yearold B-17 pilot, the “old man” of his crew who had already flown strike targets in Germany, Yugoslavia, Romania, Hungary, Austria, and Italy.

Rickey saw his B-17 explode on the ground due to the bombs it still had on board. He then lit out for Konstanz on the border of Switzerland. He managed to evade capture for six days before being spotted by the German police near the Switzerland border. They turned him over to the military, who interrogated him and then sent him to Stalag Luft I, a prisoner of war camp for airmen near Barth in northeast Germany. It was here he received the news, “Daughter born…July 19, 1944. Mother and child doing well” in a copy of a cable from the International Red Cross on Christmas Eve 1944.

Rickey was housed in a cramped room with 24 other airmen. They had a pot belly stove, a table and two benches. A B-17 navigator in the camp had access to a typewriter and would listen to the BBC broadcasts and write about the progress of the war to inform others in the camp. They knew the Soviet troops were advancing from the east, and Patton’s army was advancing from the west.

“There was hope,” Rickey said. “We knew what was happening.” Red Cross packages provided them with food until the Germans cut them off in February of 1945 after the bombing of Dresden. Then the “Kriegies” (short for Kriegsgefangener, or prisoner of war) had to survive on cabbage soup and two paper thin slices of brown bread a day. When the camp awoke at Stalag Luft I on May 1, 1945, the German guards had disappeared and a hand-sewn Stars and Stripes replaced the swastika on the flagpole. The Red Army arrived a day later. Rickey weighed 105 pounds.

“After a couple weeks of negotiations, they flew us out in stripped down B-17s. They had a crew of four instead of 10. They put 32 POWs on each airplane. You can imagine what 36 people crammed into a B-17 looks like,” Rickey said. “In two and a half days, they evacuated 9,000 of us.” That wasn’t the end of Rickey’s military story though. He went on to work as a transport pilot and as a target intelligence and war planning analyst at the Pentagon, Tactical Air Command, and Pacific Commands. In 1968-69 at 7th Air Force in Saigon, he was responsible for selecting targets for strikes against North Vietnam and Laos.

After 33 years in the military, Rickey retired in 1971 as a lieutenant colonel. But he would not forget his time in Germany. It wasn’t until a reunion in 1987 that Rickey learned the value of the strike at Memmingen. Only 12 bombers would go on to bomb the target at Memmingen. Their actual target was an underground installation where the Messerschmitt Me262 was being manufactured. The world’s first jet aircraft to be used in combat had the potential to change the course of the war. The unit was to receive the Distinguished Unit Citation for the attack at Memmingen. Also destroyed was a prototype of Messerschmit Me 264 that could reach the United States.

In 1998, the Kempten, Bavaria, Germany Historical Society erected a plaque in the village square to honor those killed during the 1944 raid. The five KIA of Rickey’s crew are on the plaque. Battlefield Archeologist Ludwig Hauber, nephew of the then-11-year-old Kurt Hauber who had watched the entire air battle over Kempten, discovered parts of the wreckage of Rickey’s plane.

“He found a rusty old machine gun with my serial number on it. Ludwig came to visit me in Arizona, and he brought 40 pounds of debris from my airplane in his luggage,” said Rickey. One of the items returned by Hauber was a damaged walkaround bottle — a portable oxygen bottle.

“These aircraft were not pressurized. We all wore masks tethered to a hose that went to an oxygen container. The walk around bottle held about half an hour of oxygen,” said Rickey. “That was a big part of our problem. At 25,000 feet, it was instant death to remove your oxygen mask.”

“People don’t understand. It’s important to tell the stories. It was a rough time of life. We have to tell the story so people will know what happened. You’ll never see an armada of 1,000 airplanes again,” Rickey said. “Can you imagine what it was like to see a bomber string 30 miles long?”

— By Kathie Dalton, Veterans News Magazine

Your donations can help preserve our veterans stories. Please donate using the button below.

Donate